Animation producer Justin Weyers describes the massive production challenges of turning Chapman’s A Liar’s Autobiography into an animated 3-D feature.

After talking to Justin Weyers for just two minutes, you begin to sense how daunting a task producing the animation for A Liar’s Autobiography – The Untrue Story of Monty Python’s Graham Chapman must have been – and how truly enjoyable a project it must have been as well. His passion for the film is infectious and his depiction of the unique challenges faced is even funnier and more interesting given his dry Aussie delivery and sense of humor.

Weyers, co-founder and director for multi-disciplinary creative agency Made Visual Studio, was the point person for integrating the collaborative work of 14 animation production studios working on 17 different scenes under the guidance of three directors who’d never made an animated feature. Making matters even more complicated and difficult was that fact that none of the studios had much if any experience working in stereoscopic 3-D. Sounds like a BBC sitcom.

No two pipelines were the same. The animation styles were different, the budget was tiny, the source material was, let’s just say, quite odd. However, bringing the last and most highly personal work of Arthur, King of the Britains, to the screen, 23 years after his death, using his own recorded voice, with an assembly of brilliant if slightly askew animators (primarily British companies, only one from the US) was just too good an opportunity for anyone to pass up.

All Great Journeys Begin with a Single Step…Or a Silly Walk

As Justin tells the story, he had worked with two of the film’s directors, Bill Jones (son of Python’s Terry Jones) and Ben Timlett as a key animator on their six-part documentary, Monty Python: Almost the Truth - Lawyers Cut. Soon thereafter they joined forces with Jeff Simpson, the film’s third director, who was attached to Graham Chapman’s audio tapes and was looking to see if a feature-film project was even feasible. After some discussion, and a funding commitment from EPIX, it was decided that an animated feature film could be the answer.

The tapes were edited down from the original three hours into something reasonable for a feature film. Fellow Pythons John Cleese, Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam were brought in to voice additional characters. An audio script robust enough to share with potential animators finally emerged.

Animating Graham’s crazy variety of characters with different styles made perfect sense. His life was very colorful. The filmmakers could have gone with only one animation house but it would have taken far too long to produce. They liked the idea of using a wide variety of styles.

There has been some criticism that the film didn’t delve more into Graham Chapman’s life, that it wasn’t more of a documentary. According to Justin, “You walk out of the film thinking, ‘Do I know Graham? Is that him?’And that’s probably how he’d want you to feel.” More to the point, that’s exactly what the filmmakers did not want to do – make another documentary on Monty Python. Whenever they weren’t sure where to turn within the story, they kept going back to Graham’s book. This film is based on this book. His partner David, who loved the finished film, said that on Graham’s deathbed, he told him “Don’t tell them anything.” He kept his private life quiet. He was openly gay and secretly an alcoholic. The other Pythons didn’t know the extent of his drinking problem until halfway through Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Ultimately, the film is about Graham Chapman, in his words. His book captured the way he wanted to tell his story and the film is true to that telling.

One example Justin shared illustrates how much effort went into capturing Graham’s essence. As he explained, “In this film, every single noise that came out of Graham Chapman was real Graham Chapman. Every cough, every pipe puff. Andre Jacquemin, who did all the sound, was the original guy who did all the Monty Python sounds on all the early records in the 60s. He went through all his records, his entire archive and pulled out everything he had from Graham Chapman. Everything he said, every ‘Uhuh’ or ‘Ahem.’ That degree of effort and underlying tone really speaks to what was so wonderful about this film.”

While the film has obvious appeal because of the Monty Python name and the Graham Chapman angle, the film also represents a rather groundbreaking integration of animated segments, done by different houses, in 3-D, that has never been done before.

In for a Penny, In for a Pound

Justin spent over two years on the film, supervising the entire animation production, working in-between the directors, who had never made a fully animated feature, and the production houses. Providing a kind of buffer.

As Justin described the dynamic, “I knew on this kind of project the animators would be working on this at 3 in the morning, pulling their hair out, as animators tend to do. But they were doing it for the love of it. This project was a lot about love.” As he explained, it was a “tremendous collaboration between the directors, myself, the animation teams, Adobe and evangelists brought in to teach people how to work in stereo. Visually I was the support structure that tied all the companies’ animation productions together.”

One of his first production missions was to create a Graham Chapman bible, to ensure scene-to-scene continuity, since every company was working in a different style on different parts of the film. According to Justin, “We weren’t sure if the animation would work jumping from style to style. What we really didn’t want to have happen was for the audience to sit down and say, ‘Oh, we just saw a short film festival.’ This character bible was an important part of making the film. We needed to ensure consistency. What Graham looked like as a boy, as a middle aged man, all the way to what he possibly could be now. It had things like what kind of tobacco he liked to smoke. Was the pipe always lit? His mother would always wear the same clothes. She’d always have glasses.”

Next, with the audio script and bible in hand, Justin contacted every animator and animation house he ever wanted to work with. He cold called them all, saying he had a feature project and was looking for people to get involved. Around 60 were interested. He talked to big companies with lots of money and independent animators just out of college working in their mom’s kitchen. One moment, he was talking to a 20 year old kid, the next moment, executive producers at Framestore.

Ultimately, he interviewed 55 companies. From there, he sat with the directors, looked at show reels, trying to match up styles and sensibilities. Initially they wanted seven different styles, 10-12 minutes each. They discussed how to modify so many well established workflows to mesh with the pipeline needs of the production. They received a considerable amount of feedback and story notes. Justin quipped, “Someone wrote back that they thought the content was quite vile. That was pretty funny.”

In the end, companies were asked to pitch which scenes they wanted to animate. Justin shared with them the entire script so they could pitch work on sections different from what the filmmaking team initially thought they’d best fit with. They received a huge number of storyboards. After some deliberations, they made their final decisions - the initial list of 90 companies was now whittled down to the 14 who would make the film.

Production began in earnest with a gathering of all the participants at Made Visual Studio’s facility, 75 people in all. They spent the first part of the morning going through the bible. Then, someone from each studio stood up and pitched their particular piece. Everyone got a good idea of how their sections would fit into the final film. That took half a day. Then the directors got up and spoke to everyone about their vision, what they loved about the project, what their motivations were. Then, David Sherlock, Graham’s partner stood up and talked about their personal relationship. As Justin describes it, “The day was just lovely.”

Many days would follow that weren’t necessarily quite so lovely. Justin and his studio took on one of the scenes themselves, so, as Justin put it, “They could share the experience alongside everyone else in trying to figure out exactly what the director’s wanted.” Typically, the first half of his day was spent animating, the second half getting up to speed and setting up the procedures and processes for the stereoscopic production. Throughout it all, he was the film’s on-call troubleshooter for anything that might go wrong. He continued, “If animators had a problem, they called me for technical support. I was often at one of their studios at 11 pm at night, working through some After Effects problem.”

Left Eye, Right Eye, Don’t They Both Go Into the Same Head?

The production was ambitious on several levels, the most obvious being that none of the participants has any real 3-D experience. Some scenes started with cell animation or line-drawn art. There was stop-motion, full CG, even oil painting on glass. Name a technique, it was used. Crank out the scenes, convert them to 3-D, sew them into a final film. This had never been done before on such a scale.

According to Justin, EPIX loved the idea of 3-D from the very beginning after reading the script. So did the final set of companies chosen to work on the film. “Every company we chose was excited about the challenge to be involved in making their style work in 3-D. Many were learning 3-D for the first time,” he explained. “We setup training days where we brought in the various compositors and went through all the things they’d need to do. We spent three months researching all the 3-D and then taught all the companies what they needed to do.”

He went on to say, “Now, with the end of this production, there are 14 companies in London that can produce work in 3-D. With these great 3-D production tools in After Effects, stereoscopic 3-D is now accessible for them to do. It’s not just in the hands of the big production houses. That was a truly remarkable outcome of this production.”

Justin didn’t force the 3-D onto anyone, trying to make them freak out about the unknown 3-D piece while they were focusing on their original production efforts. On a workflow level, 3-D made things take much longer. The film would have been done a lot quicker if it had just been done in 2D. However, according to Justin, once everyone learned how to create the stereo effect in their specific style, it was quite easy going forward. “It also took time to get the hang of how much we wanted to push the depth,” he explained. “We could move things forward and back, but for some techniques, it would make the animation almost look like cutout. We didn’t want to take away from the narrative or the beauty of the animation by making the 3-D the focus of the film.”

They could get away with much more 3-D on the animation from Superfad, which was done with Softimage, or the Mr. & Mrs: Monkeys sequence, which was done in Maya. Every 3-D effort had a different workflow, which resulted in a different depth for every scene.

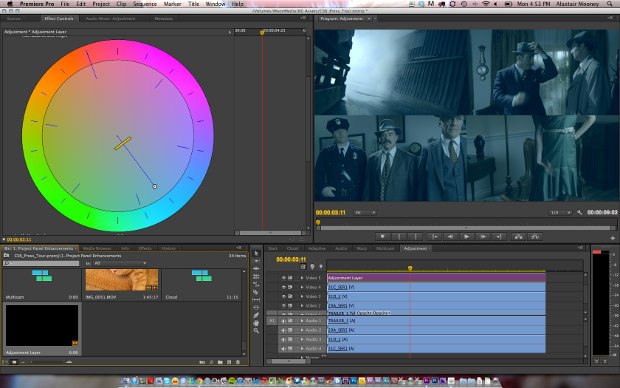

Justin’s team created another bible, a deliverable bible. It specified that everything was going to be done 2000 pixels wide and 1080 high. That gave them leeway if later they wanted to come in and fix some of the conversions, soften some things or push some things back further. Each company submitted final dpx sequences of left and right eye that they would render out. Justin then used those to make massive comps in After Effects for each section and then used Dynamic Link to jump between the program and his Premiere editing timeline. According to Justin, “If we wanted to change something, we would just double click through into After Effects and away we’d go.”

Studios sent Justin large numbers of package files with all their layers so he could make sure all their rigs were working. At the beginning his team built its own rig with Adobe’s CS4. Then CS5 came around with built-in stereoscopic, then 5.5, which is when Adobe came on board the project. With 5.5, Justin brought everyone into one stereo workflow. Each studio began using the latest versions of Adobe Creative Suite Production Premium, including Adobe Premiere Pro, After Effects, Flash Professional, and Photoshop Extended. The project literally would not have come together without the “shared” Adobe software pipeline. The standard workflow was critical. It made it easier to help people when they had problems because he could tell them exactly what they needed to do for a fix. With everyone using After Effects for final compositing, it was much easier providing support as well. However, Justin is not bashful when he says, “But God, I wish CS6 was available when we started this project.”

Justin explained how the film finally came together. “It was really quite amazing. We edited the film on one machine a Z800 HP workstation, holding an ultra fast Fusion I/O Duo, and NVIDIA Quadra 5000 graphics card. We streamlined creation of right-eye and left-eye comps making use of the 3D glasses in After Effects and writing a script by Paul Tuersley, which allowed switching eyes through multiple comps producing a smoother workflow. Also, Dynamic Link was huge, because it helped us make changes among the Adobe programs while avoiding constant, time- consuming re-rendering. Then we went to the post-production house, spent a day and a half just fixing a few things. And we were done. Doing all that editing, on one HP machine using Premiere Pro, was pretty unique.”

Justin also mentioned the ProjectChapman3D.com website that was created during the production. The site started as a repository for what his team was learning about stereoscopic 3-D. It grew into a substantial resource site and eventual home for all things related to the production. In addition, the film’s production inspired Adobe’ innovative Animate Chapman contest, where animators can download various Monty Python audio clips to use in making their own films.

Justin was honest in his assessment of the 3-D effort. “The stereo was a massive challenge. I’m not gonna lie. It was a challenge on the computers. Each company had their own pipeline. Each had its own challenges. For example one of the companies doing stop-motion, they had never shot stereo. They were getting left and right flicker. They were getting fluctuations when they were shooting left and then shooting right. It ends up the bloody neighbor was firing up their kiln and sucking up all the power and causing the spikes.”

He continued, “We lost 4 iMacs on this project. 2 literally burned up. Smoke came out of their tops. But on a positive note, everybody eventually figured out how to get their scenes done. It’s been a really amazing collaboration.”

--

Dan Sarto is Editor-in-Chief and Publisher of Animation World Network. He likes cats even though they tend to keep their distance.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.