Continuing Inspired 3D Short Film Production excerpt on story, authors Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia delve more into structure.

All images from Inspired 3D Short Film Production by Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia, series edited by Kyle Clark and Michael Ford. Reprinted with permission.

Structure

Structure refers to the logical and dramatic ways in which you assemble the plot points and character progressions of your story. In other words, it is the compelling roadmap by which the story travels from setup to resolution.

The purpose of studying story structure is not to force you to fold your creative vision into any standard formula, but to assist you in your ability to analyze and critique your own work. If something doesn't seem to be working in your story, you might be able to find the answer by studying typical time-tested structures, which might provide clues as to where your story went awry.

The Ever-Popular Three-Act Story Structure

The most standard story assembly, described in texts as old as Aristotle's Poetics, is the three-act structure a beginning, a middle and an end. Although a number of modern scholars make it a point to debunk the validity of the three-act story structure, it is difficult to ignore its significance, popularity and time-tested effectiveness. The first act establishes the characters and the goal or conflict. For example, you come home from a long day at the office, looking forward to enjoying your wife's famous fettuccini alfredo, only to discover that your dog, Butch, has already eaten your dinner! The second act involves the main action of the conflict and the climax. For example, you chase Butch around the house and yard, eventually tackling him, and just as you raise your fist to deliver punishment, you notice the neighbor's cat, Fluffy, sitting on your back porch, licking alfredo sauce from her paws. The third act, which is usually the shortest, contains the resolution. The sun sets on a tranquil evening as you and Butch sit in the backyard and share a nice, juicy, barbecued Fluffy-burger.

There are plenty of feature-length stories that contain five or more distinct acts, while many short stories have only one or two. However, the three-act structure is certainly the most common. Occasionally, an act is intentionally left out for dramatic effect. For instance, sometimes a story starts off in the middle of the second act, and the first act exists only as a back-story, revealed during the action by way of flashbacks or conversation. Your story might begin in the middle of a chase where the pursuer yells, "Hey, you stupid mutt! This is the last time you'll eat my dinner!" With this single line of dialogue, the relationship between the characters as well as the reason for the chase are revealed without actually requiring a setup. Act One indeed existed, but it is not contained within the bookends of the actual narrative. Remember this timesaving technique when you are working on your short-form script. The third act is sometimes partially left out to let the audience decide on the ultimate story resolution. These are sometimes referred to as existential endings. A third act indeed exists in these films, but the story is left with a significant loose end. Examples include The Graduate (What will Ben and Elaine do now?), The Color of Money (Will Eddie beat Vince?) and the CG short Passing Moments (Will the two train passengers ever cross paths again?).

The Instigating Incident and the Climax

Rarely do individual acts gradually segue into one another. Rather, a clear and significant event usually takes place to announce the arrival of the subsequent act. Once the scenario is established in Act One, the second act generally begins with an instigating incident that sets the plot in motion and compels the protagonist to act or respond, perhaps after an initial refusal. The instigating incident generally comes in one of three forms:

-

An action performed or a decision made by the protagonist. ("I think I'll steal somebody's wallet today.")

-

An occurrence that happens to the protagonist. ("Hey, someone just stole my wallet!")

- A significant event that the protagonist witnesses or learns of. ("I just heard that someone stole my brother's wallet!")

The incident that ushers in the third act is the climax of Act Two (perhaps the capture of the pickpocket). In Die Hard, the setting and characters are well established in Act One. The second act officially begins when the terrorists take over the party, and Act Three starts after the roof explodes.

Even the shortest animated film will still contain a beginning, an instigated middle action, and an ending climax. This can be thought of as a compressed but complete three-act structure. For instance, the first short act of the 42-second Alien Song establishes Blit sitting on a chair under a spotlight. The instigating incident is the music starting. The main action of Act Two is the performance. The climax is the falling object. And the short third act is the subsequent silence.

Remember that Act One grabs the audience's attention, while the memory of Act Three is what they ultimately take home from the experience. This is not to imply that a second act is less important than its siblings, but if you successfully hook your audience with your first act and you have a unique and captivating climax and resolution worked out, figuring out the necessary action and beats of Act Two is very often the easy part.

Exercise: Watch or recall a few of your favorite features or shorts and then try to identify the instigating incident that introduces Act Two and the climax that announces the arrival of Act Three.

Messing around with Story Structure

Some clever filmmakers get away with severely altering and reassembling the basic three-act structure. Pulp Fiction and Go bounce around between different places and times telling multiple stories, each with their own individual (yet related) three-act structure. The Usual Suspects begins after the second act, and the pieces leading up to it are told in flashback. The trip to India episode of Seinfeld, as well as the feature film, Memento, actually turn formal structure completely upside down and tell their stories in reverse. These severe structure rearrangements are often difficult to accomplish in a very short film because such intricacies require a fair amount of time to develop and ultimately connect.

Sometimes plot points are delivered in small pieces, and the complete structure is not revealed until the very end. This structure is sometimes referred to as a slowly unraveling puzzle, in which the audience is given bits and pieces along the way, but the entire story doesn't come together completely until the final piece is supplied, usually at the very end. Then the viewer often needs to spend some time putting the pieces together in his head before completely understanding the plot he's just witnessed. Atom Egoyan's Exotica and David Lynch's Mulholland Drive fall into this category. This structure generally requires the extended length of a feature film or that of a longer short to be accomplished effectively.

The Hero's Journey

No discussion on narrative structure would be complete without addressing Joseph Campbell's theories on the subject, in which he argued that every great story follows at least some variation of a rather formulaic series of events he called the hero's journey. The beats of this journey have been rearranged and modified by many scholars since Campbell first introduced them in his 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Here is a generalized description of the journey.

-

Act One. You are introduced to the seemingly unremarkable protagonist in his unremarkable home world. A call to adventure is given, and the protagonist initially refuses until a mentor appears to provide an appropriate dose of philosophy, motivation and perhaps some new weaponry or skills, whereupon the future hero begins his journey into a new and treacherous world.

-

Act Two. Some early but significant conflicts are met, as well as a few new characters who either join or attempt to thwart the journey. The final destination is eventually reached, where the supreme obstacle or villain is conquered, the stolen gem is retrieved or the princess is rescued.

- Act Three. The travelers head home along a somewhat dangerous path with the bested villain often in hot pursuit. The hero (usually) makes it back to his home world, delivering the goods, experiencing some kind of physical or spiritual resurrection and restoring order and happiness as he becomes known as the master of two worlds.

Most hero's journeys contain some element of loss. For instance, the protagonist might initially lose something or someone dear to him, thus motivating the journey. Or a teammate might get killed along the way. Or the protagonist himself might die just after completing his quest, thereby becoming the ultimate hero who has sacrificed his own life for the good of others.

Many feature films follow some variation, subset or rearranged version of the hero's journey formula, while some films, including Star Wars, Saving Private Ryan and The Wizard of Oz, actually follow the structure practically beat-for-beat. A multitude of short animated films are constructed around a compressed version of this formula, including Knick Knack, f8, Comics Trip, Recycle Bein', Pom Pom and Grinning Evil Death (see Figure 18).

It is no big mystery why hero stories are so popular and memorable. Much of our daily lives are spent solving problems and resolving conflicts. What should I get my wife for her birthday? How can I avoid road rage? How will I survive my impending IRS audit? Solving problems requires some degree of heroic effort, even if it is particularly minor in scope, risk or complication. Conquering dilemmas gives us a sense of accomplishment and the confidence to continue operating in the real world. Witnessing film characters performing even the most minor of heroic deeds gives us inspiration and sometimes specific techniques that we can apply to our own lives. Creating some form or subset of a hero's journey is certainly not mandatory, but it is definitely worth considering as a time-tested and potentially successful narrative structure for your film.

A common variation on the hero's journey is the lose/learn/win scenario, where the protagonist is initially bested by the villain, but then embarks on a journey of self discovery, often with the help of a mentor to give guidance or some new weaponry and training, which arms him to return and defeat his enemy. Examples are easy to find and include The Odyssey, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Karate Kid, Rocky III and virtually every Hong Kong Kung Fu feature.

The relationship arc is a familiar variation on the lose/learn/win theme, where boy meets girl; boy loses girl; boy grows up a bit and after some kind of heroic deed, altruistic act, uncharacteristically mature behavior, trophy-winning performance, perfectly timed speech or just plain, old-fashioned patience and determination, boy finally wins back girl. When Harry Met Sally, As Good as It Gets and Shrek are recent examples.

It is essential to keep in mind that standard story structures should be considered flexible frameworks rather than restrictive formulas. Learn and understand story structure, but then bend and break the rules to suit your particular creative vision. Just remember that no matter how closely you follow or how far you stray from standard story structure rules, the flow of your story must remain logical, cohesive and interesting. Stories are only successful if audiences can follow and enjoy them.

Pacing

Pacing refers to the timing of your story point delivery. Effective pacing will keep the mind of your audience occupied for the duration of your story. Have you ever noticed that a lethargic school teacher with a monotonous voice can make even the most exciting historical event sound as boring as nails rusting, while an exuberant and captivating lecturer can keep you on the edge of your seat while describing his uneventful trip to the laundromat? The difference is often due to an innate sense of story pacing. Each beat of your script should move your story along by making your audience want to know what will happen next without actually letting them know before it happens. Anticipation plus uncertainty equals story movement.

Pacing is an extremely important narrative component to study because bad pacing can easily confuse or bore your viewers. If your scenes fly by too quickly, your audience might miss an important piece of information and lose their connection to your story. If a scene significantly slows the action, there needs to be a valid reason for it, such as building suspense, establishing mood or creating anticipation. Make sure your scenes are long enough to clearly deliver their plot points, but short enough to move the story along at a reasonable pace. Use quick shots during action sequences and slower shots when you want to give the audience time to think.

Exercise: Watch an animated short film that you consider entertaining and analyze how the director paced out the scenes and actions to keep the story moving. How does each shot introduce, foreshadow or flow into the next? How many seconds does an average shot last? If every scene causes you to anticipate or fear the following scene, the film is extremely well paced.

A story's arc of intensity is an important pacing element to consider. Does your story start off gently, build to a climax and then rapidly return to tranquility? Or does it start off with an explosive action sequence, then mellow out for a while before exploding again at the end? If you plotted most feature films into an intensity graph, you'd see many hills and valleys, while short films generally have simpler arcs. Your film's arc of intensity doesn't necessarily have to rise continuously to be dramatic and entertaining. It can start high and then gradually diminish, or perhaps go up and down like a roller coaster. Just make sure it is not altogether flat. Study classical music pieces and rock songs for potentially interesting intensity arcs (see Figure 19).

The Short Story

Short stories are everywhere. Examples include segmented Saturday morning cartoons, narrative music videos, comic books, live action or animated short films, 22-minute sitcoms, children's picture books, multi-paneled comic strips, video game opening sequences, narrative television commercials, story poems and songs. These are all formats to examine with regard to short-form storytelling ingredients and structure.

Long-Form versus Short-Form Stories

So far, many of the story concept examples we've been providing fall under the category of the long-form narrative, which includes novels and feature films. The most obvious distinction between these and the short-form story is, of course, length. According to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, a short film is less than 40 minutes in length. As we mentioned before, most short animated films are less than 15 minutes long. We recommend a maximum of about seven minutes, but we suggest you aim for three or four minutes, especially if you are working alone.

A short story is not just a long story that gets told more quickly. Long-format stories can include large numbers of characters; lengthy establishing shots; multiple acts; complex character development; and often a few twists, false endings and complicated sub-plots. Depending on your target length, there usually isn't time to include such devices and structures in the short form.

Length, however, is not the only distinction between short- and long-form narratives. The concepts we've discussed in this chapter regarding plot, character, setting, conflict, genre and style apply similarly to both formats; but the main differences lie in complexity, structure and pacing. The trick is focus, economy and efficiency.

Variations on Long-Form Story Structures

Many popular full-length story structures are simply not appropriate for a short story. However, variations on long-form structures are often quite effective. For instance, you might be able to fit most of the story beats of the hero's journey into a 15- or 30-minute short; however, anything less will require significant pruning of the complete formula. Omitting selected beats or just using a small section are appropriate ways to successfully compress the hero's journey, as in the student films, AP2000, Recycle Bein' and Sarah from Supinfocom.

![[Figures 20 & 21] Tragedies are best served in the short form as sudden and disastrous final story moments. The slowly unraveling puzzle structure is more appropriate for longer films. [Figures 20 & 21] Tragedies are best served in the short form as sudden and disastrous final story moments. The slowly unraveling puzzle structure is more appropriate for longer films.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-20-21.jpg?itok=bchALYNP)

[Figures 20 & 21] Tragedies are best served in the short form as sudden and disastrous final story moments. The slowly unraveling puzzle structure is more appropriate for longer films.

Likewise, formal tragedies are rarely advisable for the short form because they generally require a significant length of time for the audience to fully embrace the protagonist in order to be sufficiently saddened by his demise. Ten minutes or more might give you enough time to do so effectively (f8 or La Morte de Tau); however, within the recommended timeframe of four minutes or less, a tragic twist at the end is usually best served as a less severe (and perhaps sudden) comedic moment, such as the punch lines of Snookles and SOS (see Figure 20).

Significantly rearranging the normal narrative flow of a story is also rather difficult to pull off in the short form. Films such as Pulp Fiction require a lot of screen time to tell the individual stories and then demonstrate how they all fit together. It's usually best to stick with a single, rather linear story-line with only one or a small number of characters. On the Sunny Side of the Street and Tom the Cat are rare short examples that play with standard narrative structure by telling the same short story twice, from two alternative points of view.

The slowly unraveling puzzle structure is yet another long form example that doesn't quite work in the shortest forms because it requires the pieces to be delivered slowly so viewers can sufficiently incorporate them into their evolving understanding of the story. However, a popular and appropriate short story variation on this theme is something we like to call the surprise scenario reveal, in which a single, significant puzzle piece is dropped in at the end, often revealing what the otherwise vague or unremarkable story was really about. Examples include Bunny, Funambule and Oblivious (see Figure 21). This structure can be effectively realized in as little as 30 seconds.

Typical Short Story Types and Structures

Just as a multitude of standard long-form story structures exist, some typical short-form structures seem to crop up repeatedly. Of course, short stories can be structured in any number of ways, and you should certainly feel free to assemble your plot points in any manner you choose. Always remember that lists and examples are offered as guidelines, not commands or formulas. But there are quite a few tried and true structures you might want to consider just to be on the safe side.

The Gag

Mainly because of its limited length requirements and therefore less expensive production cycles, the gag is probably the most common short animated film structure. Virtually all shorts of less than a minute fall into this category, which has several forms:

![[Figure 22] The short gag, in which something unexpected usually occurs, is a very popular short animated film genre. [Figure 22] The short gag, in which something unexpected usually occurs, is a very popular short animated film genre.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-22.jpg?itok=e1F6_F6R)

[Figure 22] The short gag, in which something unexpected usually occurs, is a very popular short animated film genre.

-

Single beat. This is a quick joke a simple setup and then a surprise twist or comedic beat. Random violence on a cute character is a common theme (see Figure 22). Short animated film examples include Snookles, Alien Song, Squaring Off and, of course, Bambi Meets Godzilla. One advantage of this type of story is that it can often be told in as few as 30 seconds. Many amusing television commercials successfully prove this point.

-

Series. This is a montage of quickly delivered punch lines. Bill Plympton specializes in this structure, which he demonstrates in films such as How to Kiss.

- Surprise reveal. The audience is unsure of the scenario of the piece (or is intentionally misled) until its true identity is revealed at the end. An example is Alex Whitney's Oblivious, in which an alien landscape turns out to be something else entirely. Keep in mind that even though it falls under the gag category, the surprise reveal is often more poignant than funny, as in films such as Chris Wedge's Bunny. It can also be tragic, as in the Oscar-nominated Cathedral, or merely explanatory, as in Anniversary or Sprout.

The Booty In this structure, the protagonist wants something (perhaps money, food, or a girl) and usually suffers through a series of often overly complicated, botched attempts before successfully capturing the object of his desire. Of course, sometimes he ultimately fails. If the object of the protagonist's affection is a moving target, a chase is often involved. Keep in mind that the goal must be worthy and not easily or immediately attainable. Examples include Fat Cat on a Diet, Knick Knack, Lunch, Egg Cola and every Wile E. Coyote cartoon (see Figure 23).

The Moral This structure uses allegory or direct finger pointing as a vehicle for making a political or social statement. Often, characters who oppose or ignore the author's agenda ultimately suffer consequences or cause others to suffer because of their negligence, as in Balance (don't be greedy), Point 08 (don't drink and drive) and One by Two (selfishness leads to loneliness). In some cases, the character(s) learn an important lesson by eventually adopting the author's view or ultimately realizing the folly of their previously misguided opposition, as in The Big Snit (don't miss the forest for the trees). Other short films that practically scream, "and the moral is," include For the Birds (he who laughs last, laughs best), Bert (don't judge people just because they are different), Passing Moments (he who hesitates is lost), Values (be supportive of your children's dreams) and Le Processus (don't be a lemming see Figure 24). Always remember that messages are best served with an appropriate combination of clarity and subtlety

The Villain In this structure, an enemy is at hand and must be conquered or evaded. Many villain stories contain several of the following types of actions, but some contain only one:

-

The stronghold defend! This action is when the villain is attempting to enter and disturb or destroy the protagonist's happy home, as in The Three Little Pigs.

-

The invasion eject! In this action, an unwanted element (such as a monster, villain, or mother-in-law) has entered the picture, disturbing the hero's happy home, and must be removed, destroyed or successfully evaded. Sometimes the protagonist does not prevail. Occasionally, the initially unwanted element is ultimately accepted. Invasion examples include The Wrong Trousers, The Cat Came Back, Grinning Evil Death, Tin Toy, AP2000 and Technological Threat.

-

The chase evade! The hero finds himself dangerously vulnerable, often in open terrain, where he is pursued by the menacing villain. Sarah is a fine example. Keep in mind that a straightforward chase scene is not usually a very interesting story. Even if it has a resolution in which the hero either escapes or gets caught, it is still not much of a story unless there is a particularly intriguing setup, the hero comes up with an especially clever escape or he somehow turns the tables on his pursuer.

- The battle engage! The hero partakes in direct physical or mental conflict with his antagonist, as in films such as Puppet, Silhouette, Polygon Family and every episode of Celebrity Death Match (see Figure 25).

The Pickle In this structure, the protagonist finds himself in a predicament (often caused by his own negligence or poor judgment), which he must solve or escape from. In many cases, a beat-the-clock scenario is involved. The Sorcerer's Apprentice is a classic example. Others include Top Gum, Locomotion and Coffee Love (see Figure 26).

The Parody

This structure is a parody of a documentary, television commercial, or any other existing property. Creature Comforts and Fishman are fine examples.

replace_caption_shorts02-27.jpg

I Wish

In this structure, the protagonist yearns for (or remembers) a happier or more exciting time or situation. Examples in shorts include Comics Trip, Le Deserteur and Red's Dream from Pixar (see Figure 27).

The Rescue

In this structure, someone (or a group of characters) shows up and saves the day. Bunkie & Booboo and La Morte de Tau are two examples. If a character rescues himself, the story either falls under the escape or pickle category.

The Journey

There are two types of journey structures:

-

External. This type of journey involves an expedition, often in the hopes of finding a better place to live. Horses on Mars is a fine example.

- Internal. This is a journey of self-discovery or growth. Often an actual geographical quest is the backdrop. PDI's classic Locomotion contains a quickly realized internal journey.

![[Figure 28] Animated shorts with unique and captivating imagery in motion and an intentional absence of significant story elements are known as fine arts films, such as Au Petite Mort from Little Fluffy Clouds. [Figure 28] Animated shorts with unique and captivating imagery in motion and an intentional absence of significant story elements are known as fine arts films, such as Au Petite Mort from Little Fluffy Clouds.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-28.jpg?itok=uGRP3Y9e)

[Figure 28] Animated shorts with unique and captivating imagery in motion and an intentional absence of significant story elements are known as fine arts films, such as Au Petite Mort from Little Fluffy Clouds.

Fine Arts

This structure consists of a non-narrative series of imagery and movement, almost always set to music. This is not a true "story"; however, if the imagery is significantly unique or interesting, it can be an extremely engaging and memorable piece. Examples include Garden of the Metal and Au Petit Mort (see Figure 28).

If you are planning to write a short story of more narrative complexity than a single-beat gag, a simple monologue or a fine arts piece, make sure your plot elements are clear, significant, interesting, and well structured. The setup must spark the audience's interest. The protagonist's goal must be worthy and difficult to achieve to make success triumphant or failure tragic. The main opposing force must be powerful enough to make the challenge interesting. The occasional roadblocks along the journey must be more than simply trivial distractions; otherwise, they won't contribute anything to the action. The ending must be satisfying and logical, and at least some element of your story must be particularly unique or there won't be any reason for anyone to watch your film (and thus there will be no reason for you to enter the production phase).

Keeping it Short

Strive to keep your film as short as possible without compromising flow and clarity. The shorter your story, the simpler it will be to produce as a film and the easier it will be to keep your audience engaged. Here are a few thoughts to keep in mind while developing your story that should help keep things short and sweet:

-

Give yourself a target length and structure your story based on a general idea of your available schedule and budget. For instance, if you have limited time and money, a single-beat gag, surprise scenario reveal or fine arts film is a safe bet because such structures can be effectively delivered in less than a minute. A six-minute film can probably contain a fairly full hero's journey, relationship arc or perhaps even a plot twist or two. A 15-minute film will afford you enough screen time for more complex story structures.

- Hit the ground running. It is often a good idea to cut to the chase as soon as possible. Start your story in the midst of an action and explain (or don't explain) later. In a feature film, the audience expects to be interested and entertained for 90 minutes or more. After the first several minutes, the viewers will begin asking questions about the story. Who are these people? What are the era and locale? Where is this story going? Is this supposed to be funny or scary? If these questions are not sufficiently addressed, confusion or boredom will set in. In a short story, however, it's all over by the time the audience starts asking such questions. Therefore, the short story writer has a decided advantage because it is often quite acceptable to leave out exposition and simply deliver compelling action with a climax or a punch line. This is especially true with animated shorts, in which the audience can expect to be taken into a fantastical or perhaps abstract world without any real explanation (see Figure 29). If you write a short animation script about a chimpanzee police officer, you can pretty much expect that your audience will buy into this scenario for at least a few minutes before they start questioning the reality of the situation. This grace period offers you an excellent opportunity to explore the farthest reaches of your imagination without worrying too much about having to explain everything.

![[Figure 29] Audiences will graciously accept bizarre, unexplained, abstract, surreal, exaggerated or fantastical scenarios and characters in a short animated film. [Figure 29] Audiences will graciously accept bizarre, unexplained, abstract, surreal, exaggerated or fantastical scenarios and characters in a short animated film.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-29.jpg?itok=rK0zEniD)

[Figure 29] Audiences will graciously accept bizarre, unexplained, abstract, surreal, exaggerated or fantastical scenarios and characters in a short animated film.

![[Figure 30] Constantly ask yourself, Why is this scene or character in my film? If you dont have a satisfactory answer, cut it. [Figure 30] Constantly ask yourself, Why is this scene or character in my film? If you dont have a satisfactory answer, cut it.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-30.jpg?itok=mM289LjZ)

[Figure 30] Constantly ask yourself, Why is this scene or character in my film? If you dont have a satisfactory answer, cut it.

-

Constantly ask yourself what you can leave out. Your short story should be like a marble sculpture, where you remove everything that is not crucial to the work of art you plan to deliver. Trace through your story and apply the word "why" to every scene, action, character and line of dialogue. Ask yourself, "Why is this element in my film?" Every component of your story needs to be a step along the path to the climax or punch line. Each scene needs to bring about a change or a movement that directly leads to your story's conclusion or the exploration of its central theme, contributes to setting a mood or provides necessary information about a character or a current event. If a scene does not satisfy one of these conditions, it should probably be cut (see Figure 30). If you have an early scene that establishes the setting of your story, ask yourself whether revealing the locale or era of your story is absolutely necessary. Sometimes it is indeed important for creating a mood, but your story might be just as effective if the setting is vague or not initially established. If you've written a particularly creative or exciting scene and you're certain that it will look really cool on the screen but it contributes nothing to your story's narrative flow, cut it. Is every minor character in your story absolutely required? Can two be combined as one? If a line of dialogue is redundant to an action, get rid of it.

-

Once you've established the necessity of every scene, analyze each one for economy and efficiency. Is every scene as succinct as possible? Is there a faster way to deliver a particular story point or characterize your protagonist?

-

Can important plot points be simply referred to in previous or subsequent scenes or acts, rather than actually being played out? Not every beat of your story necessarily needs to be shown. Often a line or two of dialogue can replace a missing scene, especially if that scene falls under the category of back-story. Sometimes it is desirable to leave out a lengthy first act where the characters and conflicts are established and jump right into the action. With some clear visuals or a couple of lines of dialogue, it's usually pretty easy to bring the audience up to speed.

-

Exaggerate. Because a short story delivers less information than a full-length narrative, it is often necessary to exaggerate its elements in the interest of clarity and efficiency. You must deliver more with less and do so in a limited timeframe. Character traits usually need to be more obvious, indicative, and perhaps rather stereotypical. Conflicts should be magnified where the forces of antagonism are often exaggerated. The stakes should be higher, the crises more extreme, the villains more direct and the odds against the hero succeeding quite significant. The more exaggerated your story elements, the less time it will take to describe or develop them.

-

Consider using text or voiceover narration at the beginning or end of your short to complete the story (but not to reveal a moral), rather than trying to contain too many events within the scope of the film itself. After all, even though most stories have a complete narrative structure unto themselves, no story exists on an island. Something always came before and something always happens after. Even in a four-hour movie, an author must decide where in the context of a larger story his sub-story will take place. If you feel that your audience requires some additional information with regard to events outside the scope of your actual film for it to stand on its own, text and narration can be effective shortcuts for creating such narrative totality.

-

Keep plot twists and digressions to a minimum. Fairly simple, somewhat linear plots without significant sub-plots are generally recommended.

- Once your story is fully formed in your head or on paper, try to summarize it in a single paragraph as if you were writing the descriptive text for the back of your film's future DVD case. If it takes more than a few sentences to describe the gist of your story, it might be too long or too complex and you should see what you can do to increase its narrative efficiency.

Exercise: Think of an event in which you participated recently a soccer game, a trip to France, an exciting night on the town, a first date or a long and complicated day at the office. Then time yourself telling different versions of the story to a mirror or to a friend. First try to tell the story in 15 minutes. Then tell the same story in seven minutes, then three, then one and then 30 seconds. Consider the ways in which you compressed and omitted certain details while keeping the story complete in each different time period. If you've written or imagined a script for your short film, apply this same exercise and see just how short you can possibly make your film without losing clarity and continuity. Remember, in general, the shorter your film, the smaller your budget and the simpler your production cycle.

Think of it this way: Suppose you have a complicated story to tell someone. You'll recite it one way if you have a few hours at your disposal. But imagine you're on a 15-minute coffee break with a coworker instead or even a three-minute break, for that matter. How will you compress the story to fit into each of these shortened time periods? Certainly not by simply talking faster. Rather, you'll likely leave out extraneous details, avoid sidetracks, and trust that your listener can fill in a few gaps with his own innate sense of continuity.

You're Making a Movie, After All

As you develop the individual beats of your story, remember to think cinematically (see Figure 31). It is not enough for the scenes of your story to seem strong on paper; they must ultimately look and sound compelling on the screen as well. If you have a scene with dialogue, consider the body language of your characters as well as the delivery and tone of their voices, not just the words themselves. If you are writing an action sequence, think about the camera angles you will use and the pacing of the individual shots. Also, as you are developing your story, constantly ask yourself whether you have the time, skills, and tools to effectively produce each scene in your chosen visual format. If a scene requires a high volume of characters and an epic landscape with many weather effects, you might want to consider simplifying or omitting it. In other words, continuously remind yourself not to bite off more than you can chew.

![[Figure 31] Remember, you are not creating a piece of literature; rather, you are planning a film, which is primarily a visual medium. Therefore, always think cinematically while you are developing your story beats. [Figure 31] Remember, you are not creating a piece of literature; rather, you are planning a film, which is primarily a visual medium. Therefore, always think cinematically while you are developing your story beats.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-31.jpg?itok=RKcVN0ZX)

[Figure 31] Remember, you are not creating a piece of literature; rather, you are planning a film, which is primarily a visual medium. Therefore, always think cinematically while you are developing your story beats.

Storytelling Pitfalls That Can Ruin a Good Short Film

Writing a good story is not easy; many things can go wrong. Here are a few pitfalls to try and avoid when constructing your short narrative:

-

Too long. We recommend keeping your short to three or four minutes or less. It is difficult enough to capture an audience in the first place, and the longer your story is, the harder it gets to maintain their attention. If you can't describe the gist of your story in a single sentence, it's probably too long.

-

Logic errors, unbelievable coincidences, and plot holes. Nothing breaks the immersive quality of a story like a glaring mistake in logic, believability or plot progression. Feature films such as Godzilla, The Last Boy Scout and Hollow Man have so many logic flaws that it's difficult to maintain believability as their plots unfold. The entire premise of Gus Van Zant's Finding Forrester is based on an extremely convenient coincidence, which is a perfectly acceptable device in a comedy or a fantasy film, but can be quite distracting in a supposedly realistic drama. Make sure your story beats make sense before you begin production.

-

Inconsistent internal logic. Most animated films ask you to suspend your disbelief to some degree. In doing so, a world is created with its own (possibly altered) rules of physics, gravity and injury immunity. Once the rules of this world have been established, they must not be broken without an acceptable explanation. If you are creating a haunted house film with ghosts that pass through walls, it doesn't make sense to allow your protagonist to successfully punch one of these otherwise intangible beings. You should feel free (and absolutely encouraged) to bend the rules of reality to suit your storytelling needs. Just remember to consistently stay within the lines of the logic boundaries you've drawn or at least have a very good reason for straying outside of them.

-

Too slow. There is no more effective way to permanently lose an audience than to bore them. This is why pacing is such an important storytelling device and should be given thorough attention when writing and editing your film. Audiences will sometimes (temporarily) forgive logic errors and plot holes in the hopes that they will be eventually be explained or resolved, but once a viewer falls asleep you may never get them back.

-

Style inconsistencies and inappropriate genre juxtapositions. A slapstick joke, such as a pratfall, in the middle of a poignant, cerebral comedy can irreparably damage the overall style of the piece and break the audience's connection to the story.

- Inconsistent character behavior. Your audience must be able to relate to your main characters or at least find them interesting to maintain their attention. If a character acts in a way that is inconsistent with his normal or expected behavior, he must have sufficient motivation to do so. Your characters need to be true to themselves and not display uncharacteristic behavior without an acceptable explanation. If Santa Claus commits murder, he had better be a villain in disguise or exist within the context of a particularly dark black comedy.

If you find you're having trouble with the structure and flow of your story, consider working with note cards. Write out each scene or story beat on a separate card and then lay them out on the floor or pin them to a wall and try out various rearrangements until you find the most effective and dramatic narrative flow.

-

Too preachy or too clever. When you are producing a moral piece, strive for subtle clarity. Try not to be too heavy-handed with your message. Audiences usually don't like to come away from a film experience with the feeling that they've just attended a lecture or a political rally. Be subtle with your message, but don't be so subtle that your film loses clarity. If you construct an intricate puzzle that comes off as a contest to see which audience members are smart enough to get your point, you'll surely lose a lot of them. Mullholland Drive is often criticized thusly, while the world of modern poetry is littered with unnecessarily intricate vocabulary and abstract metaphors masquerading as cleverness. Short animated films that deliver their moral or message with a successful combination of clarity and subtlety include Bert, Passing Moments, For the Birds, Early Bloomer, Balance and Values.

-

Manipulative. In a realistic or serious film, it is generally not considered good narrative form to tell an audience how to feel with tear-jerking cinematic tricks or all too obvious villain-identifying clues. And while shamefully manipulative features such as Philadelphia and I am Sam tend to be commercially successful, we suggest that you try to hold yourself to a higher standard of dramatic subtlety. Films such as What's Eating Gilbert Grape and You Can Count on Me, as well as the shorts Within an Endless Sky, Mouse and Le Processus invite the audience members to respond naturally because the emotional content is delivered with subtlety and moral ambiguity.

-

Not funny. Be honest with yourself. If you can't tell a joke or write funny material, don't try to make a comedy. Nothing is more embarrassing to a storyteller than a joke that fails. Study the comedic elements of short films by such directors as Peter Lord, Nick Park, Plympton, Cordell Barker, Richard Condie, Chuck Jones and Bob Hertzfeldt.

-

Predictable. If your film has a punch line, try not to give it away before the fact, and don't give your story a title that reveals the surprise ending. Imagine the loss of effectiveness if The Empire Strikes Back had been called I am Your Father, Luke. Furthermore, if you've established a particularly familiar setup, make sure it leads somewhere other than the obvious or expected conclusion. If your audience thinks they know where your story is heading and you prove them right, they will surely come away disappointed.

-

Too derivative. It is perfectly acceptable to reference or vary a story that has been told before, but there is a fine line between paying homage and ripping off. Be wary of crossing that line. If the audience has seen it all before, you won't hold their interest very long.

- No third act. Although not all film audiences prefer happy endings, most viewers expect some kind of resolution. Conflicts generally need to be resolved, journeys are preferably completed, problems like to be solved and punch lines need to be clear and complete.

![[Figure 32] A significant story object like The Wrong Trousers can serve as an appropriate short film title. [Figure 32] A significant story object like The Wrong Trousers can serve as an appropriate short film title.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-32.jpg?itok=cELdv5V5)

[Figure 32] A significant story object like The Wrong Trousers can serve as an appropriate short film title.

Titles

You can invent your film's title at any stage of production. Perhaps a great title idea is what set your creative storytelling juices flowing in the first place. If not, it's likely that an appropriate one will reveal itself to you as your production develops. Or, you might choose to wait until your script or film is completed before you think up an appropriate title. Either way, here is a list of some common title types that might help spark your imagination.

-

The name(s) of the protagonist(s). Feature films include Jimmy Neutron, Shrek and Bonnie and Clyde. Shorts include Bert, Luxo Jr., Sarah, Snookles, Fishman and Fluffy.

-

The protagonist's profession, hobby or life situation. Feature films include The Godfather, The Graduate, Taxi Driver and Blade Runner. Shorts include The Crossing Guard, El Arquero and The Sorcerer's Apprentice.

-

The villain(s) or a supporting character. Feature films include Jaws, The Wizard of Oz, Goldfinger and Alien. Shorts include The Sandman and The ChubbChubbs.

-

The setting (place, time or both). Feature films include Jurassic Park, Casablanca, 1941, Ice Age and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Shorts include The Cathedral, Garden of the Metal, Gas Planet, Within an Endless Sky and Iceland.

-

A significant story object. Feature films include The Maltese Falcon, Titanic and Rear Window. Shorts include Egg Cola, The Snowman and The Wrong Trousers (see Figure 32).

- The protagonist's name plus an associated object, setting, profession or action. Feature films include Lawrence of Arabia, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone and Schindler's List. Shorts include Geri's Game, Fat Cat on a Diet, Red's Dream, Horses on Mars and Henry's Garden.

-

The main plot. Feature films include The Empire Strikes Bac k, Home Alone and How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Shorts include The Cat Came Back, La Mort de Tau, Lunch and The Deadline.

-

The central theme of the story. Feature films include It's a Wonderful Lif e, Love Story and The Way We Were. Shorts include Values, Balance, Getting Started and Passing Moments.

- A metaphor, cliché, or a double or hidden meaning. (Be careful not to give away the punch line or spoon-feed the message to your audience!) Feature films include Independence Day, Gone with the Wind, To Kill a Mockingbird and A Clockwork Orange. Shorts include A Close Shave, Squaring Off, For the Birds, The Invisible Man in Blind Love, Point 08, Comics Trip, Top Gum, The Baby Changing Station, Cat Ciao and Framed.

If you're still stuck for a good title, try thinking of a few words or sentences that describe a significant event or plot point in your film and then consult a thesaurus for alternative words that effectively provide the same information.

![[Figure 33] Telling your story to a select audience and gauging their response can often provide you with an opportunity to fix any glaring errors in logic, structure or pacing before you enter the production phase. [Figure 33] Telling your story to a select audience and gauging their response can often provide you with an opportunity to fix any glaring errors in logic, structure or pacing before you enter the production phase.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-33.jpg?itok=WXHwvotv)

[Figure 33] Telling your story to a select audience and gauging their response can often provide you with an opportunity to fix any glaring errors in logic, structure or pacing before you enter the production phase.

Format

If you plan to create your CG short all by yourself or with a very small team of collaborators, you can generally get away with recording your story in whatever medium or format you choose. It might exist entirely in your head, on a series of paper napkins, as a sequence of rough thumbnail drawings, or as an audio recording on a portable tape deck. As long as the story is easily accessible to you and your potential team members, it is generally not necessary to follow proper screenplay structure. However, if you are planning to assemble a large team or you expect to pitch your story to a production company or your boss someday to secure funding, it might be appropriate to write out your story in standard screenplay format. Because this book is aimed at the small team or individual, we will forego any discussion on this matter and instead simply direct you to Appendix B, "Suggested Reading," where you will find a number of excellent books on the subject.

Tell Your Story to Others

During every phase of your short film production, it is often a good idea (and usually quite educational) to consider showing the status of your piece to someone else for feedback, especially if you have any doubts about the strength or clarity of your narrative elements (see Figure 33). If you're not sure whether your story makes sense or is too predictable, tell it to a friend and see what he thinks. If the response is boredom, you might want to do some editing. If the response is confusion, analyze the clarity of each plot beat and consider the fact that your story might be a bit too abstract. If you're not sure whether your story has already been told in exactly the same way, ask around.

![[Figure 34] Objective self-criticism is perhaps the most effective production tool a filmmaker can possess. [Figure 34] Objective self-criticism is perhaps the most effective production tool a filmmaker can possess.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-34.jpg?itok=C9ncJKzu)

[Figure 34] Objective self-criticism is perhaps the most effective production tool a filmmaker can possess.

And be selective about your critics. If you seek feedback from everyone you know, your work could become collaboration, and you'll risk losing sight of your initial artistic vision. The desire to avoid being the victim of plagiarism or to deliver a surprise ending often makes it tempting and desirable to keep your ideas to yourself. These are valid concerns, but don't always expect that you'll be the best judge of your own work.

Keep in mind that oddly enough, negative feedback is often more helpful than compliments as long as the criticisms are constructive rather than merely insulting. Remember that the worst possible reaction is indifference. If most of your critics love your piece, you're probably on the right track. If they think it stinks, most of them should be able to tell you why, and you can then choose to review and perhaps repair the sources of their complaints. If you get no reaction whatsoever you've delivered mediocrity, which is the ultimate sin for an artist. Even a bad story is better than a mediocre story because at least the bad one will get a reaction.

Objective Self-Criticism

If you truly want to keep your idea hidden from external scrutiny until your film is completed, you need to develop the ability to critique your own work as objectively as possible (see Figure 34). One way to accomplish this is to give yourself some distance. Set your story aside for a few days and then, when you review it, try to pretend that someone else wrote it. Apply the same critical eye you would use on another writer's work. Ask yourself tough questions about the piece.

-

Is it paced well?

-

Are there any plot holes or logic errors?

-

Are the story beats clear, and does each action contribute directly or indirectly to the central theme, premise or message of the story?

-

Is the ending sufficiently satisfying?

-

If it's supposed to be funny, is it?

-

How many acts does it contain?

-

If it has three acts, can you identify the instigating incident that ushers in the second act and the climax that brings about the third?

-

What is the protagonist's goal? Is it worthy of a story?

- What is the central obstacle? Is it sufficiently challenging?

And while this might seem like an obvious point, if you're not interested or entertained by your story, nobody else will like it either. Be brutally honest with yourself. If your story has problems, go back and fix them. Don't let yourself believe that your viewers might miss or forgive your errors. Even a child will notice a glaring logic hole or a weak ending.

![[Figures 35 & 36] Dan Bransfields Fishman (top). Wilhelm Landt and Joachim Bubs On the Sunny Side of the Street (bottom). [Figures 35 & 36] Dan Bransfields Fishman (top). Wilhelm Landt and Joachim Bubs On the Sunny Side of the Street (bottom).](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-35-36.jpg?itok=L6FG9yeY)

[Figures 35 & 36] Dan Bransfields Fishman (top). Wilhelm Landt and Joachim Bubs On the Sunny Side of the Street (bottom).

A Few Examples

Now that we've discussed the elements of storytelling, let's analyze a few examples of CG shorts that contain good stories that are well told.

Dan Bransfield's Fishman is a hilarious parody that effectively combines originality with familiarity (see Figure 35). The story opens in the midst of an action, where a pair of bumbling superheroes, loosely based on Batman and Robin, fail to accomplish their intended mission after getting caught up in the frustrating and all-too-familiar task of trying to parallel park their oversized car. The humor succeeds mainly because the "hero" arrogantly believes himself to be a successful and observant crime fighter, while his actions tell a very different story. Poking fun at arrogant stupidity is a very popular and effective form of comedy. The ridiculous costumes and exaggerated vehicle design also contribute to the humor of this film. At only two minutes and 19 seconds in length, this film moves along at a solid pace, with suitable music adding to its overall appeal. The style is an interesting and amusing contrast between the dark, film-noir look of a 1930s gangster drama and the silly and overly colorful designs of the main characters and their fish-mobile.

On the Sunny Side of the Street, by Wilhelm Landt and Joachim Bub, tells a very simple and straightforward story but achieves appeal and originality with its style and structure (see Figure 36). The style is that of an early twentieth-century silent film, using black and white imagery, old-fashioned clothing and props, simulated film projection imperfections, and suitably nostalgic music. The structure of this film is interesting because it tells the same story twice from two different points of view, and then combines these alternate perspectives together at the end. This relatively uncommon structuring helps to make this otherwise straightforward story into something quite original.

Jason Wen's f8 is a 12-minute science fiction tale that combines a gritty visual style with appropriate pacing, interesting camera angles and somber music to form a tense and cautionary tone with an air of impending doom (see Figure 37). The story gracefully comments on the perils of technology gone astray and the loss of individuality and humanity. The central theme is somewhat familiar to science fiction fans, but the delivery and details are especially unique and interesting.

![[Figure 37] Jason Wens f8. [Figure 37] Jason Wens f8.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-37.jpg?itok=Z4uq7nv2)

[Figure 37] Jason Wens f8.

Summary

While the commercial success of many blockbuster films might suggest otherwise, strong story elements are more important than strong production elements. A story can be defined as a series of interconnected or related events, which, through conflict, significantly change a scenario or a character. A short story is one that delivers such events with economy and efficiency. The four basic story ingredients are plot, character, setting and conflict. A character in a setting with a worthy goal, a reason why it can't be immediately achieved and a subsequent plan with complications is an extremely common formula for a story premise. The way a story is told is equally (if not more) important than the story elements themselves. Storytelling tools include genre, structure and pacing. Remember that a short story is not just a long-form story told more quickly. Rather, you must apply significant differences in structure and pacing. Economy and efficiency are the keys. Linear plots with a single or few characters are recommended. When constructing your short script, think cinematically and apply the word "why" to each scene, character and action, making sure every element in your story is there for a reason. Remember that all rules of story construction and delivery can be bent and broken as long as you do so creatively, not just because you simply want to appear clever or different. In Chapter 3, "Character Development and Design," we will discuss characters, which are typically used to channel the events and emotional impact of a story to an audience.

To get a copy of the book, check out Inspired 3D Short Film Production by Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia; series edited by Kyle Clark and Michael Ford: Premier Press, 2004. 470 pages with illustrations. ISBN 1-59200-117-3 ($59.99). more about the Inspired series and check back to VFXWorld frequently to read new excerpts.

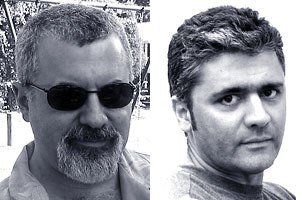

Authors Jeremy Cantor and Pepe Valencia.

Jeremy Cantor, animation supervisor at Sony Pictures Imageworks, has been working far too many hours a week as a character/creature animator and supervisor in the feature film industry for the past decade or so at both Imageworks and Tippett Studio in Berkeley, California. His film credits include Harry Potter, Evolution, Hollow Man, My Favorite Martian and Starship Troopers. For more information, go to www.zayatz.com.

Pepe Valencia has been at Sony Pictures Imageworks since 1996. In addition to working as an animation supervisor on the feature film Peter Pan, his credits include Early Bloomer,Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle, Stuart Little 2,Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone,Stuart Little, Hollow Man, Godzilla and Starship Troopers. For more information, go to his Webpage at www.pepe3d.com.

![[Figure 18] Comics Trip, Pom Pom and Recycle Bein are simplified versions of the heros journey. [Figure 18] Comics Trip, Pom Pom and Recycle Bein are simplified versions of the heros journey.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/attached/2221-shorts02-18.jpg?itok=e9ADdmZQ)

![[Figure 19] Examine the arc of intensity of existing songs and short films. [Figure 19] Examine the arc of intensity of existing songs and short films.](http://www.awn.com/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/image/featured/2221-inspired-3d-short-film-production-story-part-2.jpg?itok=o4-7Vdbr)