Twenty years ago, Who Framed Roger Rabbit revitalized the animation industry as a bold experiment, looking back as well as forward, as it turned out. AWN marks the historic occasion by reminiscing with Richard Williams, Don Hahn, Tom Sito, James Baxter and Ken Ralston.

Has it really been 20 years since the release of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Twenty years since the given-up-for-dead feature animation industry stood up and said, "Plplplllease, you gotta give me another chance! Come on, Raoul!"? Twenty years since Andrew Farago made his parents, older brothers and any available adult with a drivers' license chauffeur him to the next town for multiple viewings of his new favorite film. Not to mention 19 years since he rushed out to see Honey, I Shrunk the Kids as soon as it hit the local theater based solely on the inclusion of seven new minutes of Roger Rabbit animation? (OK... and the comic stylings of Rick Moranis.)

So, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Farago interviews three key members of the animation department: Associate Producer Don Hahn and animators Tom Sito and James Baxter, while AWN Senior Editor Bill Desowitz speaks with Animation Director Richard Williams and Visual Effects Supervisor Ken Ralston.

Don Hahn

Andrew Farago: How did you first become involved with the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? What convinced you to take on the project?

Don Hahn: I had just finished work on The Great Mouse Detective as production manager and Peter Schneider was called to take a meeting at Amblin to discuss the animation on Roger Rabbit. Peter was new to the department so he asked that I start going with him to talk to Bob Z [Robert Zemeckis] and the producers about the project. After that I was pulled in slowly to start to manage tests, then to go to London to work with Dick [Richard] Williams and his studio and eventually to live in London for almost two years to oversee the animation as associate producer.

AF: Can you describe your role in the production of the film?

DH: I produced the animation. There were three major elements of the production: the live-action shoot, the animation and the magic that ILM did at the end to combine it all together. The studio in London was a combination of key players from Dick Williams' studio, four key animators from Burbank and a team of gypsy animators that we hired from around the world to come to London to work. I hired Max Howard, who was a brilliant manager, and together we built a studio around Richard and the crew to deliver the film.

AF: Please talk about your experience in animation prior to Roger, and how that compared to the technical challenges that you faced on that film.

DH: I had worked on Pete's Dragon as an assistant director to Don Bluth, so I knew some of the challenges of the live action/animation combination. What was really hard about Roger is that Bob Zemeckis wanted to break all the rules of animation in live action. He wanted, rightly so, to make a modern movie that happened to have animation in it. He moved the camera, which required all the work to be done on ones. He created difficult lighting situations and dressed characters like Jessica in glittery costumes. The animation studio in London suffered from a slow learning curve, but so many of the artists were used to working on TV commercials for Dick that they were used to being innovative and knew how to problem-solve. By the end of production, we were sailing and the work was flowing out of our Edwardian Factory building in Camden Town.

AF: Disney animation underwent a renaissance with the release of The Little Mermaid, in 1989, but there are many who point to Who Framed Roger Rabbit as the big turning point for Disney's animation department in the late 1980s. Do you agree with that statement? Can you describe the pre-Roger and post-Roger Disney Studios?

DH: Pre-Roger was The Great Mouse Detective, which was a really good harbinger of what was to come. It was one of Ron [Clements] and John [Musker's] first directing efforts, and the success of that film led them to Mermaid and me and others to Roger Rabbit. I think Roger Rabbit was the film that reminded the audience how much they loved good animation, especially the great animation of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones. It was the first animated film to really draw in an adult audience, not just kids.

DH: Animated shorts are expensive and usually don't turn a profit for the company, so there have to be other reasons to create them.

Certainly for the Roger Rabbit shorts, the idea was to keep the characters alive until the sequel could be prepared. The first and second shorts flowed pretty quickly from a series of original ideas that sprang up right after we returned from making the movie in London. The third short took a little while longer to produce, but it was made in our Florida studio at the time and was a terrific film. It became clear by the time the third short came out that the sequel was going to be years off and with three shorts in the can, it was time to hold for a bit until the second movie became a reality.

Of course, we are still holding.

Tom Sito

AF: How did you first become involved with the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? What convinced you to take on the project?

Tom Sito: I had been working on some TV series in L.A., but not feeling particularly challenged. I went to London to animate on some commercials with Eric Goldberg. The London scene then was jumping with interesting projects. While there, I went up to visit Richard Williams, who was an old friend of mine. Dick took one look at me and exclaimed, "Oh Sito! You must come work on this!" He hired Pat [Connolly] and me on the spot. And that was that.

AF: How long had you worked in animation prior to Roger? How had your previous jobs prepared you for your work on Roger?

TS: I'd worked about 13 years. I had worked with Richard Williams on at least three other occasions, and we were good friends. Dick's standards were so high, I even took the fact that he talked to me as a compliment. He simply had no time for mediocrity. I knew working on this project would be an event. When I read the script, it was the best script I had read in years. I could already see the movie in my mind. I was so used to the bland, PC, homogenized Hollywood product, that when I read this, I actually went in the next day and said to Robert Zemeckis with incredulity:" This... is... good! Are we seriously going to make this?" Bob looked a little insulted, coming from screenwriting. " Of course we are." And I replied, "Far out."

AF: Disney animation underwent a renaissance with the release of The Little Mermaid, in 1989, but there are many who point to Roger as the big turning point for Disney's animation department in the late 1980s. Do you agree with that statement? Can you describe the pre- Roger and post- Roger Disney Studios?

TS: I do believe Roger Rabbit was the beginning of the great 2D renaissance at Disney. Before that feature animation was rudderless, stewing in its own juices and not knowing what to make of its new ownership. The Great Mouse Detective kept the doors open, but morale was not good on Oliver & Company. No one yet understood what Katzenberg & Co. really wanted out of them. There was resistance from the more hard-core Disney loyalists. There was the competition from Don Bluth and Spielberg producing An American Tail, which had great success that surprised everyone.

After Roger Rabbit's success, it seemed anything was possible. I think Andreas [Deja] entered his mature personal style on Roger and James Baxter was discovered out of school. Nik Ranieri also came from this group. A cadre of Dick's London animators returned to Burbank like a flu shot for the spirit of the crew. Oliver picked up, then The Little Mermaid convinced us that the success was no one-shot fluke.

AF: Which characters did you animate? What animators did you find yourself studying most often while preparing to work on the film?

TS: Because I joined the crew later than most, I asked Dick where was I needed the most. He answered: "Weasels. No one wants to do them." So I did a lot of weasels, including the scenes where they all die. I also animated some of the gorilla bouncer at the Ink & Paint Club, and a lot on the finale.

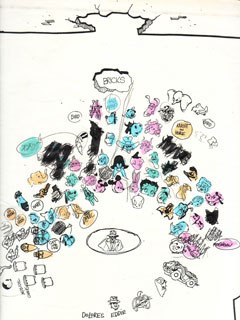

I animated Woody Woodpecker, Sylvester, Yosemite Sam and Dumbo. I did the last shot of the picture: sc.235/57, I'll always remember it. One hundred characters, 28 runs under the camera for 38 feet, (45 feet is 30 seconds), 14 levels. All singing, all dancing. Zemeckis wanted it to look like the last shot of Hitchcock's The Birds, except with toons. I also got to animate some of the last voice work of Mel Blanc, doing Sylvester. He died two months later. I studied Rod Scribner, Clampett's Sylvester from Kitty Cornered, Dick Lundy's Woody Woodpecker.

AF: How much time did you spend working on the film?

TS: About eight months.

AF: Did you have much interaction with the live-action department, or were the animators fairly isolated?

TS: The live action was pretty well done by the time we were crunching on the footage. But cinematographer Dean Cundy, as well as Ed Jones, Steve Starkey and Ken Ralston of ILM made themselves available for any problems or support. We were flattered when Ralston (then in charge of ILM) said to us after, "That was the hardest picture I had ever done. The spaceship pictures we got down, but making this toon noir look real, that was tough."

AF: Was working in a London a big adjustment for you and the other animators?

TS: It was. We all speak English, but it is still a different culture. Even the can openers don't open the same. But it was a pretty international crew. We had artists from Ireland, Holland, Canada, France, Germany, Zimbabwe and more. It was a real Légion étrangère. By the end we were a pretty tight-knit family.

We hung out together at the pub, and took care of each other. London's Time Out magazine joked that all the artists wandering around Camden Town in their Disney U.K. crew jackets looked like an army of occupation. When the film premiered in NYC, my birthplace, a bunch of Brits came out for the opening and Pat and I got show them my town, as they were our guides in Old Blighty.

AF: How demanding was Richard Williams as a director? What lessons did he impart that are still with you to this day?

TS: Dick is the most demanding yet exciting director I ever worked with. Every time our paths crossed, I felt my technique improved. Before he ever started lecturing, he was the world's greatest student of animation technique, and he infused all his young artists with the same desire to study the master animators. Dick never drove an artist harder than he drove himself, but he did drive himself very hard! He was the quintessential G.I. general. He always wanted to outdo himself on the next scene, and he encouraged us to outdo ourselves. That is his greatest legacy.

One more anecdote: I recall after all the hoopla and effort, the day of Roger Rabbit's opening finally came. Now it was up to the public. I was driving through my parents' old neighborhood in Brooklyn when I stopped at a traffic light. Roger was playing at the Canarsie Theater across the street. I saw three little scruffy kids, like extras in a Fat Albert movie, crossing in front of my car.

I heard one say about the film, "Hey, did you see dat?" And the other replied, "Yeah, it sucked!" I was horrified! Oh no!! But later that night, back in Manhattan, when I saw the triple lines of ticketholders held back by police barricades in front of the Ziegfeld Theater, and the line extending down the block around 6th Avenue, I knew we had a hit on our hands.

James Baxter

AF: How did you get involved with the production?

James Baxter: I started on Who Framed Roger Rabbit in the summer of 1987. The film was already well underway, the opening Maroon Cartoon was already complete, and Richard Williams had already moved his entire operation to Camden under the umbrella of Walt Disney Animation UK. A few friends and me heard about the project during our first year at West Surrey College of Art and Design where we were studying animation. A project like Roger doesn't come to London very often, so it was a once in a lifetime opportunity for us.

AF: And what was your role in the animation department?

JB: I started out on Roger as an in-betweener and then was on Andreas Deja's clean-up crew. During this time I was doing animation tests and showing them to Andreas. Eventually, they started giving me little pieces of animation to do, until I was made an animator around the end of 1987.

AF: Which characters did you animate?

JB: I animated mostly weasels, but I also did a few Roger and Jessica shots. Dick Williams had always been a hero of mine when I was still at school, and it was largely because of him that I took a chance and quit school (after one year) to go work on Roger.

AF: What was it like to work with Richard Williams? What lessons that he taught are still with you today?

JB: Dick was a great guy to work for. He led by example and always expected very high quality out of everyone. The big thing I learned from him early on was to "follow the brief." In commercial art, you are always dealing with other people's expectations, and you can't just do whatever you want. I learned how to ask questions of my superiors so I could always give them what they were expecting (and maybe a little bit more).

AF: Do you see Roger Rabbit as a major turning point for Disney, and for animation as a whole?

JB: As far as Roger being the start of the renaissance at Disney in the late '80s, I think it would have happened anyway, with the change in management at the studio, but there is no doubt in my mind that Who Framed Roger Rabbit was a big jump start. It also brought a lot of new blood to the studio (including me).

Richard Williams

Bill Desowitz: So, what is your take on how Roger Rabbit came about?

Richard Williams: It was very obvious that Disney and Spielberg went into this temporary marriage because Disney owned the book but Spielberg had the 15 to 30-year-old market. And Disney had lost it. So it was very clear that Disney was the bank and Spielberg was the creative drive, and then Disney, as we went along, came in and gave us animators and became more creatively involved. And we knew it was going to work right from the start: we did a camera test at ILM with the rabbit. Bob Zemeckis was worried that we couldn't get the lighting effect, so they set up an obstacle course to see if it would work and I animated the rabbit and Ken Ralston oversaw the test. He was just fabulous to work with. Anything we sent to him they improved because they were doing the final optical printing. You know, there was only one computer shot in the whole movie: a motion control that Ken did where Jessica Rabbit went around the old comedian, Stubby Kaye. Otherwise, everything was sticky tape, pens, pencils. When I went to ILM back then I was just shocked that it was the same as us: rubber bands, sticky tape, erasers.

BD: What was it like working with Zemeckis?

RW: The thing with Bob was that I never saw anybody learn so fast. He learned all about animation in a sort of twinkling. And he was always very clear about what he wanted to do. Otherwise, the only thing was time pressure: there was so much work in it. I used to go to the door to my office and yell, "Draw faster!" So it was challenging all the way down the line but you had to do it fast just to get the thing through.

BD: And what was fun about it?

RW: The fun was we knew it was going to work. But it sure wasn't a party. I remember I bumped into Bob one Thanksgiving or Christmas, and I think I was going to Canada and he was going to America, and I said: "Jesus Christ: it's working!" And he said, "Absolutely." And I said that it felt like throwing darts at a target and we seem to be hitting the target. And he agreed.

BD: What was Zemeckis like with animation?

RW: When he came to me, all the animation directors that he had spoken to -- and there were quite a lot of them -- said we need a locked off camera so the animators wouldn't have to keep drawing things on ones or turning things. And I'd already done some commercials where I violated all the animator's rules and had a moving camera. Bob said he wanted to shoot a modern movie where the camera moves, and I said, "Exactly: shoot a modern movie and we'll draw a rabbit in it." But he said, "All the animators say that's difficult." And I said, "Those lazy bastards! We're supposed to turn things: that's our job!

BD: So he approached it like a live-action movie.

RW: Absolutely. And Bob would shoot it, we'd blow up the big photo stats and stick 'em on the drawing board and draw a rabbit on it.

BD: And what was it like working with the animators?

RW: Well, they were all fans and I could cast the ones most appropriate for the character. And we started with just a handful. In fact, at the end, we ended up with huge amounts of people. But I'd say there were 10 that were really doing the film. And I animated a ton of stuff on it. I did the drawing on every scene, that's for sure. I animated the first minute by myself. I was heavily animating throughout and I ran a repair shop, which was always full. So that's how it was: it was a rush, really, a high adrenaline thing from the beginning.

BD: What was it like being based in London?

RW: I said you have to do it in London. I had my studio there (which I had been running for nearly 25 years), so we had the whole team in place. And then, strangely enough, our lease was up on the building that we were in. And then, coincidentally, then came Spielberg and we moved to a big place in Camden Town, and that's how we started. And we piled on more people. And at the end of the picture, I was liberated both between Disney and Spielberg setting up Amblin animation and taking away our animators. I was sick of carrying a large studio. I wanted to just do the work.

Ken Ralston

BD: You're currently working on Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland, which is a very ambitious hybrid of live action and CG. Are there some interesting parallels with Roger Rabbit?

Ken Ralston: Yes, Alice reminds me in a vague way of Roger. There's the March Hare: we have a two-scale rubber version of him for actor reference, not lighting reference because there are so many virtual environments. And we had to build Toonland from scratch, which is like Underland or Wonderland. Roger changed animation. When I first got the script from Bob, I thought it was awful. It seemed like an odd choice for him. Little did I know, it was just the start of a series of odd choices.

BD: When did you realize that this was going to be special?

KR: I went to a meeting at Amblin and there were these sculptures and they all had a Tex Avery look and I knew what they were going for. We shot this weird test at ILM where we came up with some things that would push buttons. It was ridiculously hard but I enjoyed it. We laughed at dailies constantly. It came at the exact time in my career. I was tired of spaceships. And it was what I loved: a Tex Avery/Chuck Jones homage with a bizarre Chinatown story.

BD: Talk about the main technical challenge.

KR: It was important to blend in with real world. This was not a CG hybrid of a cartoon. Hanging on to the aesthetic was important to me. I knew Tex, having worked in commercials with him. We built two VistaVision cameras for the movie at ILM. They didn't roll serious film in the VistaVision cameras until they shot the movie. That's how hectic it was: chasing down Hope Street in L.A. before Christmas and going back and forth to England. Those kinds of things drove me nuts -- having to be so on top of everything because everything is an effects shot. You don't know the requirements until you do it. With Bob, he's very flexible. What a mind. And trying to keep up with his ideas is painful at times.

BD: How has your Roger experience helped you on Alice?

KR: I couldn't have been on Alice without Roger. To be a part of Roger and how it touched people is cool. These tools are great, but, as I keep saying, it's how you use them. I can at least try to pre-empt issues that come up. It's a fast shoot, and I anticipate problems so they don't blow up in your face. The variables are endless -- technical and aesthetic.

Andrew Farago is the gallery manager and curator of San Francisco's Cartoon Art Museum and the creator of the weekly online comic serial The Chronicles of William Bazillion.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN and VFXWorld.