What should have been an easy review ended up not being so easy.

Dear Pixar,

You would have thought that this would have been the easiest review for me to write. After all, I’m a cognitive scientist and Inside Out took place on my turf, an area I can claim expertise. Instead, I’m left with a blathering pile of emotions, which I guess is appropriate given the subject of the animation.

There was much to delight in the simple joy of seeing how you took full advantage of animation’s ability to visualize scientific metaphors. Cognitive and neuroscience research is replete with references to “trains of thought,” “memories colored by emotions,” “storing memories,” “memories crystalize,” “abstraction and fragmentation,” “neuron communication,” “neuron fibers” and “neural pathways.” Common English language refers to “emotional charges,” “pushing my buttons,” “explosive feelings” and “bundle of nerves.” You just had to turn figurative language into images.

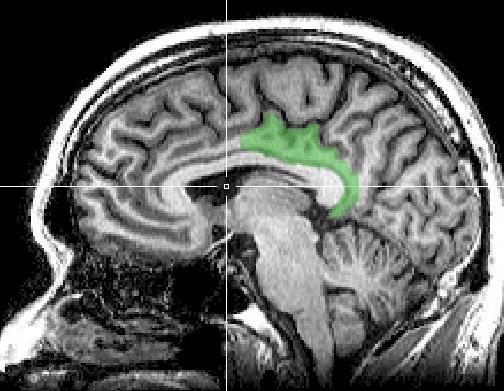

In fact, forget about kids; this film should be required viewing for any student in the cognitive fields. For example, I’d quiz my students on where they think the unidentified emotion control center is in the brain. (I assume this may be the cingulate cortex, specifically the amygdala). Or maybe ask where the memories would be stored? (I’d go with the medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus and amygdala).

Indeed, knowing how much research went into this film, I can only hope your animators were given honorary degrees in neuroscience.

Yet some things are never convincingly dealt with:

- Riley is not really the main character of the film, she is more of the setting in which the emotional characters are the prime players

- All the emotions except “Sadness” are nuanced, expressing degrees of intensity and valence, and even exhibiting mixed emotions. “Joy” in particular shows hints of sadness, fear, and anger

- The “islands of personality” are really social schema that structures Riley’s memories and emotions of events and facts

Ironically, the biggest problem I had with the film emerged from the biggest compliment I can give. It goes something like this:

A main metaphor in the film is “communication.” Brilliantly taking creative license with the comic-strip motif of thought bubbles, thought becomes crystalized into memory bubbles that are colored by emotion.

Of course, graphic thought bubbles, where the character’s inner speech is made visible to the reader, won’t work in a film. And while emotion neurons do communicate via chemical and electrical signals, the viewer needs a way to eavesdrop on what’s being “said.” So it makes perfect sense to give the emotions mouths, to speak to each other in a language the viewer can understand.

But halfway through the film, having checked off the cognitive motifs the film presented, I started paying closer attention to the way the emotions were, as they say, fleshed out.

Pixar brilliantly combined the metaphors of “thought bubbles,” and the actual bubble-like containers (vesicles) of chemicals released in the neuron that are jolted into action, communicating electro-chemical signals from one of a billion neurons via possibly more than of 250 trillion circuits (synapses).

The microscopic appearance of neurons and synapses, and the visible close-up view of human skin, creates a literally scintillating effect. The neuron fibers covering the emotion’s bodies quiver with energy, especially “Joy.” The fibers don’t mimic hair that moves because of air; they mimic how neurons discharge and absorb chemicals and electric volts.

This is a very powerful notion handled in an exquisitely subtle way. The feeling was not unlike biting into my favorite chocolate, Chuao’s “Firecracker.” It’s dark chocolate laced with pepper and a teeny amount of popping candy. The main taste is richly decadent chocolate but, after a few seconds, you get a subtle yet lingering explosion in the mouth. It’s an aftertaste that literally pops up surprisingly, even though you know it’s going to come.

Hence, some disappointments.

There was no room for “surprise,” one the six basic emotions named by Pixar’s chief advisor on emotion, Paul Ekman. That omission makes for awkward expressions when the emotions react to various events.

And even more fundamental is not dealing with “love.” I can’t blame Doctor for not tackling “love” when scientists are having difficulty in identifying “love” as being either an emotion or a drive, like hunger. But without “love” there would be no family “island,” no social attachments. Her parents didn’t comfort Riley when she lost a game because they’re sad for her; they’re sad for her because they love her. Riley doesn’t want to return to Minnesota because she’s sad; she’s sad because she loves and misses her friends. A continuum of love for family and friends will define Riley’s values and how she relates to herself and society.

When “surprise” hooks up with “joy” and “love,” you also have the basis for aesthetics.

There are points to debate, but the bottom line is that I “loved” this film.

Sincerely,

Janet Blatter, PhD

Sagittal slice image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cingulate_cortex#/media/File:MRI_cingulate_cortex.png