Peter Plantec interviews Stanford professor Ron Fedkiw and Scanline Production GmbH head Stephan Trojansky about their advances in fluid dynamics.

Computational simulation is growing daily in importance to the VFX world. Yet those of us who are artists in the field mostly have no clue how simulations work; we just set the parameters and keep tweaking until we get it right. But the clockwork beneath those simulations arises from a complex synergy of ideas from absurdly brilliant minds.

Although there are dozens of people creating advances in computational fluid dynamics the simulation of gases and liquids Ive chosen to look at two leaders of the pack. One is a distinguished American assistant professor at Stanford University, Ron Fedkiw, who just received the Significant New Researcher Award at SIGGRAPH 2005. The other is a distinguished German vfx filmmaker and head of Scanline Studios in Germany, Stephan Trojansky. The former comes from an academic/engineering background, while the latter hails from a practical filmmaking one. Each in his own way is a special genius leading the way. Both have artistic vision to go along with their technical prowess.

Why is fluid dynamics so important to the VFX world? In the simplest sense, the things we can realistically simulate with the best fluid dynamics are very expensive to duplicate practically. Both water and fire effects are difficult to manage, time consuming to set up and can be dangerous to actors. Plus, water is usually cold, causing nipple pucker and whining on the set.

By combining limited practical with extensive digital effects, everybody benefits. Since big ocean effects, massive explosions both terrestrial and in outer space, are very much in vogue, computational simulation of fluid dynamics is expanding what is possible, while reducing costs and danger for this entire class of shots. Unfortunately, up until very recently, digital water and especially explosions has been woefully detectable by ordinary human eyes. We have been suspending disbelief, but only just barely. All this has now changed.

The point of computational simulation is to push beyond the detectable into the realm of transparency. Water effects that you cant tell from real require much more than technical algorithms; they require an eye for the real world, reference footage study and a great deal of technical artistry which is no longer an oxymoron.

Consider the difficulties. Ocean transparency alone is a big issue, as is believable shading. Then consider translucency and subsurface light scattering and surface micro texture. Then there are the issues of spindrift, bits of flotsam and foam sloshing, along with wind blown spume and even drips and drops falling off of leaping fish. I havent even mentioned the essential subject of how to achieve real looking wave behavior, integrating all the things that impact that shape such as sea floor and wind. Then theres achieving believable flow and spatter when moving water hits irregular objects like rocks and people and trucks. Available packages wont do it for you. The subject is vast.

Fedkiw (pronounced Fed-co) is way more than an assistant professor of Computer Science. He is a VFX visionary with the technical genius to recreate nature through simulation. With a long list of awards for excellence, Fedkiws work and that of his students have appeared in many Industrial Light & Magic movies over the last five years, including the lava in Revenge of the Sith. In fact, Fedkiw is a part-time consultant with ILM. He appears to have a unique mind that is constantly visualizing ways to simulate Mother Nature, better, faster and prettier.

Fedkiw and his graduate students consistently come up with interesting and useful pieces of physical simulation code. Much of this code has been customized at ILM to meet special needs: Our Physics Based Modeling code (PhysBAM) has been incorporated into ILMs [new] Zeno infrastructure and given many custom user controls, he explained. We use it for all the big fluids shots in movies like Terminator 3, Star Wars: Episode III, etc. ILM is dedicated to making its tools as transparent to the artists as possible and to help them become more collaborative, so the custom work on PhysBAM, as used in this world-class pipeline, is significant.

He added that his students share in the credit as well: Yes, I took direct action to ensure that *all* code we write in my group is BSD licensed, so every student here walks out the door with all of his and everyone elses as well.

As a result of Fedkiws dedicated efforts, many of his students begin consulting in the VFX industry while still in his program. In fact, two of his students are currently consulting at ILM, one at Pixar and two at Intel. Two more have recently left for academic jobs after consulting at Sony. All in all, his program seems to be incubating the future of high- level VFX software designers.

If you go to his webpage (http://graphics.stanford.edu/~fedkiw/), youll see that Fedkiws water looks damn good, and he addressed what distinguishes his work for the pack:

Most fluid solvers just try to simply solve equations. We strive to better mimic the key aspects of the fluid dynamics. For example, with smoke, fire and explosions, this would be the vorticity, which is the swirl or spin effect. Thus, weve written papers addressing different aspects of vorticity such as confinement, vortex spin particles, etc. For water, this also includes the way the surface behaves and thus we invented the particle level set method for better surface detail.

(As a note: particle level set approach is an improved method of computing the shape and flow of the boundary interface between two fluids such as water and air, while preventing mass dissipation common in standard Navier-Stokes solutions not so important with gasses, but with liquids its critical.)

Fedkiw then speculated on what the big issues in fluid dynamics are: For film, its about bigger and better simulations with more and more realism. Crashing gigantic photorealistic waves on a beach would be awesome. Also, fire and explosions can be done with CG, but are still often done practically. So for him, one of the big goals is to be able to do fire and explosions with such realism that doing these things in practical is no longer viable. That could well save producers money while again making things safer for the crew.

As for oceans, there are several ocean disaster pictures on the horizon, and, considering the state of this art, I suspect PhysBAM will be plugged in via Zeno, to some, if not all of them. Fedkiw confirmed: PhysBAM, as now incorporated into Zeno, will be used in many films not only for fluids but also for rigid bodies, cloth, flesh, etc. Some of the original work I can talk about was smoke for Jurassic Park III, while the more recent stuff includes Terminator 3, Pirates of the Caribbean and the last Star Wars movie. It was even used to create the dragon fire in the trailer for the upcoming Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire movie.

Kim Libreri has been assigned as ILMs vfx supervisor on Wolfgang Petersens Poseidon Adventure, due out in May 2006. Since he will be using Zeno for the big ocean effects, I can surmise that we will be seeing some very big PhysBAM based ocean vfx there. Also, young Christopher Paolinis, Eragon is slated for ILMs touch early next year. Its a wonderful dragon story complete with dragon fire and smoke. PhysBAM will most likely be used for many effects besides dragon breath, including cloth and dragon flesh. And you should know that ILM vfx supervisor Bill George will be using PhysBAM on Pirates of the Caribbean II for even more advanced ocean stuff than you can imaginemaybe even surf crashing.

Trojansky is somewhat of a legend in European vfx. He recently became the first vfx person ever asked to sit on the German Film Board, and has garnered numerous film awards for his spectacular work, which has been featured in dozens of European films and TV as well as SIGGRAPH Electronic Theaters. Hes also a popular and frequent speaker at conferences and universities both here and in Europe.

In his third year studying architecture and visualization at Stuttgart University, Trojansky needed to get out and do something important, interesting and creative. I started teaching myself CG and I wanted to study but left university I simply couldnt wait to work on the pictures instead of doing exams, he offered.

Trojansky took a job at The Frauenhofer institutes Virtual Reality Lab working with CAVE applications using four-screen surround video. It was fun but he wanted more. Intrigued with the visual world of film, he took a position at Scanline Productions vfx department in Munich (www.scanline.de).

I started at Scanline eight years ago and during this time Ive been working on more than 40 movies as an artist and supervisor. I grew with the company over the years and that gave me a lot of freedom. I had an opportunity to help decide about further developments. This resulted in my becoming head of research and development, and I have been focusing primarily on software development and innovation.

One of my first tasks six years ago was destroying a massive hydro dam in full CG. This seemed to me like the greatest challenge in CG. We had to cheat everything with volumetric particles and stuff like that, but a few projects later I got so sick of seeing particles. They simply dont work like the real world, so I decided to find new and better concepts for the creation and rendering of fluid-like effects.

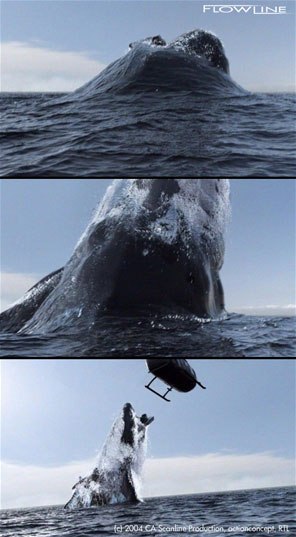

I didnt understand any academic papers covering those topics, and I knew that theres no help from outside, so I drew from my programming skills from school and started a new software system called Flowline. I was working somewhat independently with my own ideas on this. I knew that it would take a few years until there was enough memory and CPU power to do full computational simulations of water and fire the way I wanted. Now after four years, we have the CPU and GPU power and memory we need. With currently six developers working on it, Flowline has become a complete operating system for all kind of simulations, and we use it heavily in our productions.

Trojansky added that Flowline is designed to create all kinds of simulations for vfx within one tool. It covers everything from simulation to final rendering of water, splashes, bubbles, oceans, fire, explosions, smoke and clouds.

For me, the most important rule is to be innovative... I never understood the complex papers that contain mostly formulas. Finally, it is the passion about visual effect simulations that gives my team new ideas every day. With six developers now,its painful that we cant transfer all our ideas into the software as fast as they come to us.

Is Flowline made up of several separate engines or is it well integrated beneath a unified interface?

It is important to make things as seamless as possible, Trojansky continued. In fact, both fire and water have a lot in common but have also completely different aspects concerning data structures or rendering features. Flowline connects them all together in one simulation. For example, you can have fuel dripping from an oil rig into an ocean, catching fire and finally leading to an explosion. Its all done in one very efficient pass. For me, the biggest task creating simulation software is to take the step from a simple demo to a world-scale photorealistic visual effect shot.

Scanline, like ILM, works closely with their artists to develop a practical, transparent interface, so they dont get stymied. For example, Scanlines interface uses realtime GPU rendered feedback so the artists can view and tweak things very quickly, not having to wait for long renders.

We use our own proprietary ray-tracing concept together with commercial raytracers to achieve photorealistic renderings very quickly, even with gigantic data structures, Trojansky suggested. Step by step, an artist can rebuild the nature within Flowline with full control over all physical laws. Recognizing that portraying nature may require art to be bigger than life, artists can tweak until it looks right.

Trojansky exclaimed: Every day Im surprised with the ideas and pictures the artists come up with. Now our compositors can concentrate on fine-tuning CG elements instead of trying to fit perspectives and lighting of expensive footage into a plate.

What about the prospect of making Flowline more widespread throughout the industry?

Right now it is still an internal resource, Trojansky acknowledged. As we have released some information, we are getting many requests for us to license Flowline. My answer is: Im open to suggestions. Flowline gives us a significant edge in the industry after many years of R&D time, but there are circumstances under which we would consider licensing it. I am definitely thinking about it.

Fedkiw and Trojansky have never met, and come from two different worlds with two entirely different sets of motivations, yet theyre both making a major impact on what we see on screen.

Fedkiws interest seems to be in the engines of nature. His approach is to understand underlying processes and model them mathematically as closely as possible, casting out all bugs until the final shot accurately reflects nature. Its these processes that fascinate him, not the job of building an integrated pipeline from scratch.

Trojansky, on the other hand, is a filmmaker driven by the final moving image. He believes nature can sometimes be improved upon with a little artistry. His Flowline is a complete package with both accurate physical simulations and tools for artistic intervention.

Both men are closing in on the production of what may be todays Holy Grail in oceans: crashing, believable surf. As one of them said: The crashing wave swelling around the lighthouse poster behind my deskonce I can recreate that, then Ill retire.

With dragons, oceans, flooded cities and at least one mermaid, followed by several nasty storms and more than 2,223 explosions in space scheduled for 2006 release, we can expect to see the hand print of each of these two giants all across the board.

Peter Plantec is a best-selling author, animator and virtual human designer. He wrote The Caligari trueSpace2 Bible, the first 3D animation book specifically written for artists. He lives in the high country near Aspen, Colorado. Peters latest book, Virtual Humans is a five star selection at Amazon after many reviews. Your can visit his personal website.