The Harry Potter supervisor reviews the challenges of Part 1 and a tidbit about prepping Part II.

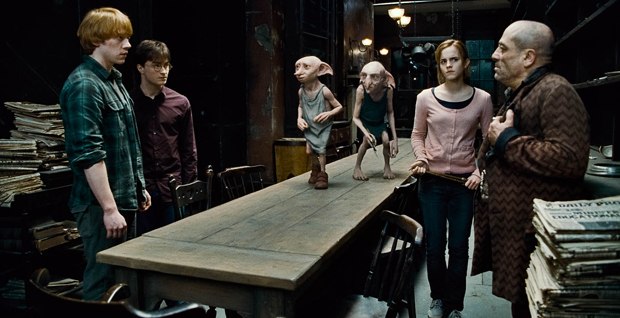

Tim Burke briefs us once more on the CG environments and characters that comprise the penultimate Potter installment, which includes the participation of MPC (the opening seven Potters motorbike chase; Nagini, the snake); Framestore (Dobby & Kreacher); and Rising Sun Pictures (the Horcrux).

Bill Desowitz: As you've said in the past, Part 1 offers a dramatic departure away from Hogwarts. What does it represent as far as VFX accomplishment?

Tim Burke: The environments have been used extensively to continue the idea of this huge journey that the actors have taken. A lot of the environment work, obviously, has been done on small sets on the backlot of Leavesden Studios. We've had to extend those and make this journey a believable event through visual effects by taking you to all these different places, and they didn't leave Leavesden Studios very often. So that was one of the big tasks, further developing our tools and the photorealism for creating those environments.

And I think the development that we've done with the creatures has come with more animation finesse. We've been able to develop a natural character within the creatures -- Dobby and Kreacher and Nagini -- giving them real life. It's very important on this film to empathize with Dobby during the big death scene at the end. It had to be as emotional as if it were an actor playing a character dying. We had an incredible level of detail put into those animations. Everyone would be able to see the moment when life passes out of Dobby and it's actually done in the most subtle way with the study of the face and seeing, literally, the light switching off in his eyes. It's very, very well done. And, for me, it's that kind of humanistic believability of character that [takes it to a new level of achievement].

BD: What were the most difficult challenges?

TB: I think the creation of the Horcrux and then the destruction in the forest was a difficult one. Conceptually, it was quite hard to find the creature, if you like. It was something that was very subjective, something that David Yates had some definite ideas about, but not easy to realize in concept work. We used a combination of techniques to create a swirling mass of evil that was summoned from the locket. But then David want the additional creation of faces and different ages of Voldemort be portrayed in a very abstract way. His reference was the self-portraits of Francis Bacon, which are distorted and grotesque. It was very complex, and, fortunately, it came right at the end of the production schedule. I mean, what does it look like if you're destroying somebody's soul? Which was the brief on that one, and so it's difficult to find some of those things. As it is, I think we created something quite dark and powerful, but it is open-ended. And quite often, you almost have to do the work before you know the end result.

BD: What was the breakthrough on that?

TB: I think when we got a lot of the Houdini fluids working and that gave us something we could all latch onto. And we were using facial capture data to drive the Voldemort faces and that plugged in quite well. It was all about trying to integrate them into this big, swirling mass. But there was no real eureka moment -- it just pushed us to the line.

There were other very big, complex sequences: the seven Potters motorbike chase, the sheer volume and size alone was a difficult one to deal with because it involved so many CG environments. Again, I'm not sure how many people realize how much was CG and how much was real. From the moment they take off Privet Drive, a partial set within a set extension and then into full-CG cloudscape environment and then they crash back down into the tunnel, which, for the most part is CG, but some of the traffic is real and some is CG, and full CG environment outside. It was quite a mammoth job for everyone.

BD: Even though you're dealing with a fantasy world on the outskirts of our real world, it has to look believable and consistent.

TB: Yeah, absolutely: you've hit the nail on the head. And that's what we've strived for. It can't be a fantasy world because the audience has to believe the wizarding world exists. So if you go too fantasy with the design of the buildings, the environments and the effects, then it would remove the believability of this parallel world. So we've tried to make the effects real and grounded and have a sense of volume and presence. You can immerse yourself in the story, and with Part 1, the wizarding world was invading the muggle world. So that was another great shift and to see the cross-over.

BD: What's it been like splitting the finale into two parts?

TB: For production purposes, we've treated it as one big film. So, we started our previs on sequences in Part 1 and Part 11 simultaneously. In 2009, we were actually finishing off the sixth film but got the previs up and running so we could develop some of the big sequences for Part 1 like the motorbike chase. But we were also prevising a lot of the major battle sequences in Part II because the shooting schedule dictated that some of those fell a lot earlier than sequences that had to be filmed for Part 1. For instance, we didn't shoot the Horcrux scene until May 2010. Of course, we've been developing R&D for Part II since back in 2009, when we started the digital build of Hogwarts. Because, in order to achieve everything we needed for the massive fight sequences and the level of destruction, and to have flexibility later on, we decided, for the first time in the series, to do away with the miniature and turn to a full-CG environment of Hogwarts. So that's been ongoing for more than two years now and has been an absolute godsend. There have been so many changes in design and in shots and sequences and how the shots are being used. But because we have a CG model, we've just been able to go in and re-previs, re-block out. And, with the level of detail of our model, we can pretty much fly into any part of the school. So we've got complete freedom.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.